Building Dots: How to Eat to Become a Circus Performer

Absinth Circus show in Las Vegas.

Nutrition for the Circus

The goal is simple - become a professional circus performer. Going through THIS, a new question emerges: how do I eat for performance as an aspiring circus artist? How does a top-tier athlete fuel their efforts? Now, exploring this question there are many resources to consider. My approach is two fold. First, define the general principles of nutrition that should, or at least could, be followed to achieve health. Then, adjust these baseline principles in accordance to the needs of the specific sport and inputs required to be effective in that sport. Unfortunately for me, I do not currently have a dedicated team to build the plan for me. So I’ll have to build it myself. This is the purpose of this article. It will outline my nutrition strategy as a circus performer. It may get longer (hopefully shorter) over time, but will serve as a living document.

So this article is going to be tactile, a very much “what to do” article. I’m writing it for myself and those that follow in the footsteps of heading towards an aspirational athletic goal. My goals will be different, but I hope the approach is useful for you or at least comparative - which could spark some conversations!

Goals, goals, goals

The overarching goal is to become a professional circus performer. There are many different ways to be considered a professional performer, and at this point I really have no idea how to narrow down this goal besides getting a job in a professional circus troupe. But that goes beyond the scope and is too far into the future to determine at this point. First, we need to translate all that stuff into something tangible. My intuition tells me that I wish to start towards becoming an aerialist, which means I need to be light enough but strong enough to execute the skills. I do not yet have access to a professional community to define this, so I will have to work off of a baseline. Luckily, the New England Circus School has a series of definable prerequisites to get into a professional level circus school. There are seven categories.

Part 1: Strength

Part 2: Stability

Part 3: Flexibility

Part 4: Handstands

Part 5: Ground Acrobatics

Part 6: Partnering

Part 7: Coordination

Some of this is a mixture of strength, like isometric holds in handstands, and other parts of it are in there. But how does this translate to nutrition? Well, certain athletes tend to look certain ways and fit within a statistical distribution from the mean. As a simple example - gymnasts are rarely super large people. It makes sense, just as NBA players are little.

So if I am going to start towards a foundation in something, I’ll have to start training towards the demands of the sport. Unfortunately, gymnastics is a lighter persons’ game. Getting airborn will likely require some fine combination of strength relative to my bodyweight.

Me, I’ve always tended to be heavier (and more flexible) than the average bear. As of 12/15 I weighed in at 97 kilograms (213 lbs). When I was a competitive level CrossFit Athlete, gymnastics felt best at 85 kilos (about 185 lbs). So one goal to consider is cutting down some body fat while doing my best to maintain lean body mass - due to needing this mass for performance.

To secondary goal of this is to be able to protect my existing muscle mass, keep my connective tissue healthy (a problem in my family), and to be able to build the relative skills I need to build as a developing circus artist. Those skills are likely stability and flexibility focused, which we’ll focus on in a different article.

So in the scope of establishing a nutrition strategy over the next year, I’d like to:

Cut down from my current weight to 85 kilograms over the course of the year. That is 12.72 kilos, or approximately 28 lbs.

Protect my surgical sites from my two hip arthroscopies and maintain the connective tissue health as I get stronger and more flexible.

Build muscle mass specific to circus and develop my skillsets in tandem with the muscle mass building.

But to do that, I’ll need to have a baseline of nutrition to work with and then tweak the nutrition around my specific athletic goals. So this article will have two sections. The first will explore basic nutrition and the second will then apply the particulars around how to eat for performance as a circus athlete.

The philosophy around eating

I’d like to admit when I got into this racket of weightlifting and Crossfit I was 16-years old. Like many early Crossfitters, there was only one nutritional philosophy - “The Paleo Solution" by Rob Wolf. At the time, this was a god-send to me and helped me lose 50-pounds in the course of something like four months. And as many of us back in those days found out, this low-carb approach made any sorts of performance pretty miserable. I forget what the specifics of the paleo diet were but there aren’t enough sweet potatoes in the world to meet the carbohydrate requirements of a person who trains multiple times a day. Back then, I calculated everything and put them into boxes with a label maker saying what it was and what nutrition it had.

These days, my approach is more holistic. Get the nutrients I need, avoid the things that I’m allergic to, and give myself enough fuel to do the workouts of the day. Now, nutrition is tricky because there are hundreds, ok, thousands of different dietary recommendations out there. I am not a biologist, a nutritionist, or anything like that. So the challenge is decide which to believe in an what to do with that information when you have it. Early on, I was influenced by authors such as Catherine Shanahan, physical therapists like Kelly Starrett, Robb Wolf, etc, and found that that all had similar messages around nutrition.

What to eat and what to avoid

Eat whole meats, veggies, and fruits. Grains are ok but not ideal if you can’t tolerate them. Milk is ok but can be dense in sugar. And eat the organs (of animals, not your enemies). On this point, Catherine Shanahan’s Deep Nutrition argument made the most sense to me, and it is what I will base my nutritional strategies off of today.

It’s actually pretty simple. Baseline human nutrition should be composed of (here is her summary) -

Meat on the bone

Fermented and sprouted foods

Organs and other “nasty bits”

Fresh, unadulterated plant and animal products

This is somewhat hard to execute with some habit adjustment, but I like it. In my - admittedly limited - experience this isn’t terribly hard once you learn how to work with organ means (think braunschweiger, liver, pâté) and get decent at making bone broth. Her book outlines her argument beautifully here. I think of these principles as things you want to make sure you’re getting on a regular basis. Meat, daily. Organ meats, ** cough cough **, at least a couple times per week. Fermented and sprouted, daily. Fresh, uncooked ingredients, daily. Cook the ingredients the slow way, ideally in an slow cooker or air fryer. Simple as that.

Now, let’s get tactile! Like hand to mouth tactile. For this, I am going to borrow from Catherine Shanahan’s 2nd book “Dark Calories: How Vegetable Oils Destroy Our Health and How We Can Get It Back.” Now, it may sound like I’m trying to just peddle her books. I promise, I’m not. A, I don’t have a following yet to where that makes any sense. And B, she just makes an argument that I currently buy into. So my focus as an athlete is execution, later I’ll continue to assess if it makes sense or needs addendums.

First one must eat like a healthy human and then factor in the specific around fueling for athletic performance. The avoid list is pretty simple for me. There are general things to avoid and then there are specific things to avoid for me in particular.

I’ll start with the generals and then get into my specific body. In no particular order, avoid the following as much as possible -

Any food containing these vegetable seed oils: Corn, Canola, Cottonseed, Soy, Sunflower, Safflower, Rice bran and Grapeseed (see why)

Corn syrup

Added sugars

Anything that had to be created in a laboratory for my consumption (dairy vs. ultra-processed coffee creamers)

Most alcohols on a regular basis (unless the plot demands it)

Specific to me, I am intolerant to gluten, large spikes in blood sugar, and some forms of shellfish. So I should avoid those as much as possible. The occasional indulgence won’t kill me, but as a baseline 90%+ of the time these should be avoided.

How much?

The complex question of what precise nutrients to consume are outside of the scope of this article. However, it still always boils down to how much of what and when. Three meals a day is still my go to and the nutrients should be spread across those meals with little to no snacking in between (will get into why this could be wrong for athletes, in a second).

For baseline health, we want to get enough nutrients to sustain muscle mass, keep us happy, and have our bodies functioning well. There is a plethora of possible combinations to do so, but above we’ve established that we get to pick from the above four pillars of human nutrition. So the question is how much of the the above should I eat. Quantities will vary, but if the goal is a healthy body the main components I have to look at are protein intake and vegetable intake. From the book Built to Move, which borrows from the 800 gram challenge heavily, a baseline nutrition will consist of:

0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of bodyweight. (Note this is higher than government recommendations)

800 grams daily of fresh fruit and vegetables

There are myriad of specifics that can go into narrowing down this further. So I met with Scott Luper, ND to determine how to further narrow down these restrictions. His recommendation were to:

Diet - eat 30 different vegetables and fruits.

Breakfast

- Protein 2-3 oz - The best - fish, wild game, organic meats, eggs, soy, beans, nut.

- Veggies - 8 oz, mix root and other veggies. limit root veggies to 1/2 of meal

- 6 oz fruit, Eat at least 4 oz berries daily

Lunch

- Protein 2-3 oz

- Vegetables - 12 oz

- Fruit 4 oz

Dinner

- Protein 2-3 oz

- Vegetables - 10 oz

There a couple insights to his recommendation. One, the protein count is inconsistent with the book’s recommendations. Two, the vegetable and fruit intake totals well over the 800 gram requirement (1.76 lbs). Three, there is a huge amount of variety in the fruit and veggies in this diet. During our 1-on-1 Scott said to aim for 30 varieties per week of fruits and vegtables. The idea being that if you continue to get variety you will never fall short of any particular micronutrient. Four and finally, it’s important to note that this prescription also falls into the recommendations of the four pillars of nutrition.

So - as of right now - 205 grams of protein spread across three meals (approx. 65 grams per meal) and 800 grams of fruit and vegetables as a day while avoiding the above list of ingredients. For me, and to meet the harder of the pillars, also tend to make bone broths and try to eat various forms of organ meats during the week. This is highly unstructured in my case as long as I get them in.

How does this change to eat for athleticism?

This is going to be where it gets tricky. No two days are exactly the same as an athlete and, as a result nutritional needs will differ for me based on the dynamic interaction of how much training I’ve done, how much I’ve moved that day, and how well I’ve slept the night before. That’s why the above strategy is so crucial to establish as a baseline. If I hit the 205 grams of protein (or whatever my body weight is) and the 800 grams of fruits and vegetables daily, that’s a win.

The question still remains - how does training as an athlete change my nutritional requirements to support that? Well, the good news is the variables won’t change. We have the four pillars to guide us and the baseline 205-800 gram rules to guide default behavior. Again this can get complicated quick, so let me set a guiding principle around my nutrition as an athlete.

I am 30-years old learning a new skillset of circustry (which itself has skillsets within it that need to be learned). The overarching goals are going to be consistent progression in skillsets and longevity. Let me translate longevity into something more tangible. Don’t get hurt.

This section is worth a books worth of explanations, but my task is to do my best to sort good knowledge from bad knowledge and then translate it it into simple actions for me to apply in my own training. The majority of which I will do by attempting to translate from the lessons of High Performance Training for Sports (HPTFS), a multidisciplinary tome of a textbook written by experts across various subjects in professional sports. Straight from their concluding paragraph -

When planning a performance nutritional strategy, the main framework should consider the three elements discussed in this chapter: total, type and timing. No magic bullet supplement or current fad can ever take the place of this foundational structure. Without it there is no plan.

So let’s talk about training. That will help me determine the total, type, and timing of nutrients. As a performer I am a true beginner, with a background in Crossfit and ice hockey. Coming out of a recovery, I want to learn and build a foundation as much as possible without being overly narrow in my initial approach. So my training over the first year will be primarily focused on getting lots of exposure across a wide-variety of circus areas. From roughly January, 2025 to May, 2025 I will aim to do the following:

Dance: Find a dance studio and dance 3x per week

Strength and Conditioning: do Crossfit 4x per week with a goal is to change body comp and get down to 185 lbs

Recovery and Flexibility: Yoga: 3x per week

Develop Baseline circus skills: attend aerial view circustry as much as possible. Starting with classes twice per week.

To meet these demands from a nutrition perspective requires a general understanding of the duration of these activities. I will get into that in a moment. But I’ll start with the non-negotiables from the textbook,

To maintain athletic function and optimal performance, the energy requirements of the athlete must be understood. A chronic mismatch of intake vs. expenditure can have negative effects on health.

……

Protein intake should be 1.3 to 2.0 grams per kilogram of body mass per day, ingesting around 20 to 30 grams every 3 to 4 hours, depending on overall body mass.

Overall fat intake for an athlete should be 1 to 3 grams per kilogram per day from quality sources, but actual intake largely depends on the athlete, sport and goals.

Notice how the baseline carbohydrate recommendations aren’t in there? I’ll get to that. Let’s start with total intake. HPTFS recommends a variety of different sources for determining my resting metabolic rate based on cost, availability, and the like. As an independent athlete, the easiest calculation for me to apply is the Cunningham equation (link). I weigh 95 kilograms and have a body fat percentage of around 18%, itself an estimate as I don’t have calipers yet. With this equation, I then adjust the numbers based on my daily activity level, which includes biking 3x per week to and from various locations.

Based on the results of this calculation, my resting metabolic rate RMR (the calories you burn while you're at complete rest) to be around 3542 kcal per day. The goal of the initial calculation is to figure out our total requirements day by day, then translate them into simple habits that I can follow out to fuel my activities. We can calculate this as the Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE, pp. 85 online). This is equal to the Thermic effect of exercise (TEE) plus the Resting Metabolic rate (RMR) plus Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) and the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). Sound like a bunch of nerd calculations? It is! I won’t bother to go into them but the total of all of these equals how much I need to roughly eat.

The Cunningham Equation seems to calculate Non-exercise thermogenesis in it already so I won’t bother with that. That leaves us with RMR plus TEE + TEF. Translation: baseline metabolic rate plus caloric needs for training plus caloric need to offset the cost of digestion.

The basic idea is to figure out how much intake vs. output is needed. Thermic effect of food is apparently hard to calculate. So we’ll cut that. That leave us with the Thermic Effect of Exercise, which we’ll come back to later.

Protein and Fat

For now, some baseline calculations based on the heuristics above. Let’s start with protein and fats. I am going to be cutting some initial weight (9kg, 20lbs). To do that we want to maintain muscle mass and cut off body fat. According to HPTFS -

“… athletes should consume higher amounts - 1.3 to about 2.0 gram per kilogram of body mass per day - due to increased expenditure and physical demands, ingesting around 20 to 30 grams every 3 to 4 hours, dpending on their over all body mass.

…………

the upper end of this range (or higher in sme cases) should be used when in a caloric deficit to minimise the loss of lean mass. (pp. 93)”

From a protein perspective, that would total to 190 grams of protein daily, 15 grams under the Build to Move recommendation. That’s equivalent to 750 kcals of energy ingested.

Now onto fats. The recommended daily fat intake for a 95 kg athlete is 95 to 285 grams (1 gram to 3 grams per kg of body weight). Converted to kCal, this totals to between 855 to 2565 kcal. That’s a pretty big range, which should allow for quite a bit of nutritional flexibility depending on the needs of the day. As I progress, both the protein and fat requirements will likely decrease to stay in a relative caloric deficient. But the same heuristic rules apply.

Now, carby carb carbs

There is amount, timing, and type of carbohydrates in the diet. Amount is measured in grams, timing is when, and type is loosely classified as low glycemic vs. high glycemic carbohydrates. There is a lot to this subject, most of which is related to performing in competition and doing multiple sessions in a day. I don’t have a vigorous performance schedule yet, so I will focus my carbohydrate question around supporting adaptation and changing body composition towards the desired 85kg goal.

I risk getting too numeric here. So will try to keep as simple while maintaining a general strategy. We know that the RMR is roughly 3542kcal per day. Next we have to estimate how many calories we’ll need to execute the training of the various sessions. I have no perfect way to do this, so I’ll estimate using Chat GPT. Here is what it came up with:

Assumptions:

Dance: Moderate-intensity dance class, approximately 300 calories per hour.

CrossFit: High-intensity workout, approximately 400 calories per hour.

Yoga: Moderate-intensity yoga class, approximately 200 calories per hour.

Circus Skills: Moderate-to-high intensity, depending on the specific skills, approximately 350 calories per 90-minute session.

Calculations:

Dance: 300 calories/hour x 3 sessions/week = 900 calories/week

CrossFit: 400 calories/hour x 4 sessions/week = 1600 calories/week

Yoga: 200 calories/hour x 3 sessions/week = 600 calories/week

Circus Skills: 350 calories/1.5 hours x 2 sessions/week = 466.67 calories/week

Total Calories Burned: 900 + 1600 + 600 + 466.67 = 3566.67 calories per week.

Now, how do we account for these calories via nutrients? Which is most appropriate? From High Performance Training for Sports (HPTFS) -

“At low to moderate intensities, most of the required energy can be provided by a combination of fat from within the muscle (intramuscular triglycerides) and body fat (adipose tissue) and carbohydrate (muscle glycogen and plasma glucose) substrates. As intensity increase, a greater demand is place on carbohydrate as the main source of fuel to produce energy (pp. 88)”

Now I could account for performance and such but that’s a future that hasn’t happened yet. Instead, let’s account for variation of carbohydrate requirements in training. We have a mixture of moderate, moderate high, and high intensity activities. All of these will vary depending on training days and how many sessions are done per day.

As a general recommendation, I will adjust based on the similarities of the high-intensity and moderate to high intensity training recommendation of HPTFS.

There is a distinctive range here of possible carbohydrate intake for me as an athlete. On top of this, it is an estimate based on a high-intensity training of rugby players, which could overestimate my actual carbohydrate requirements an earlier stage athlete training circustry. Now there are specifics of timing of nutrients, but we’ll get into that another time. These these ranges have to be adjusted based on my body composition desired change - which bring me to the next question, how do you cut weight effectively as an athlete? Before we get there, let’s look at the potential overall intake ranges. They are summarized below -

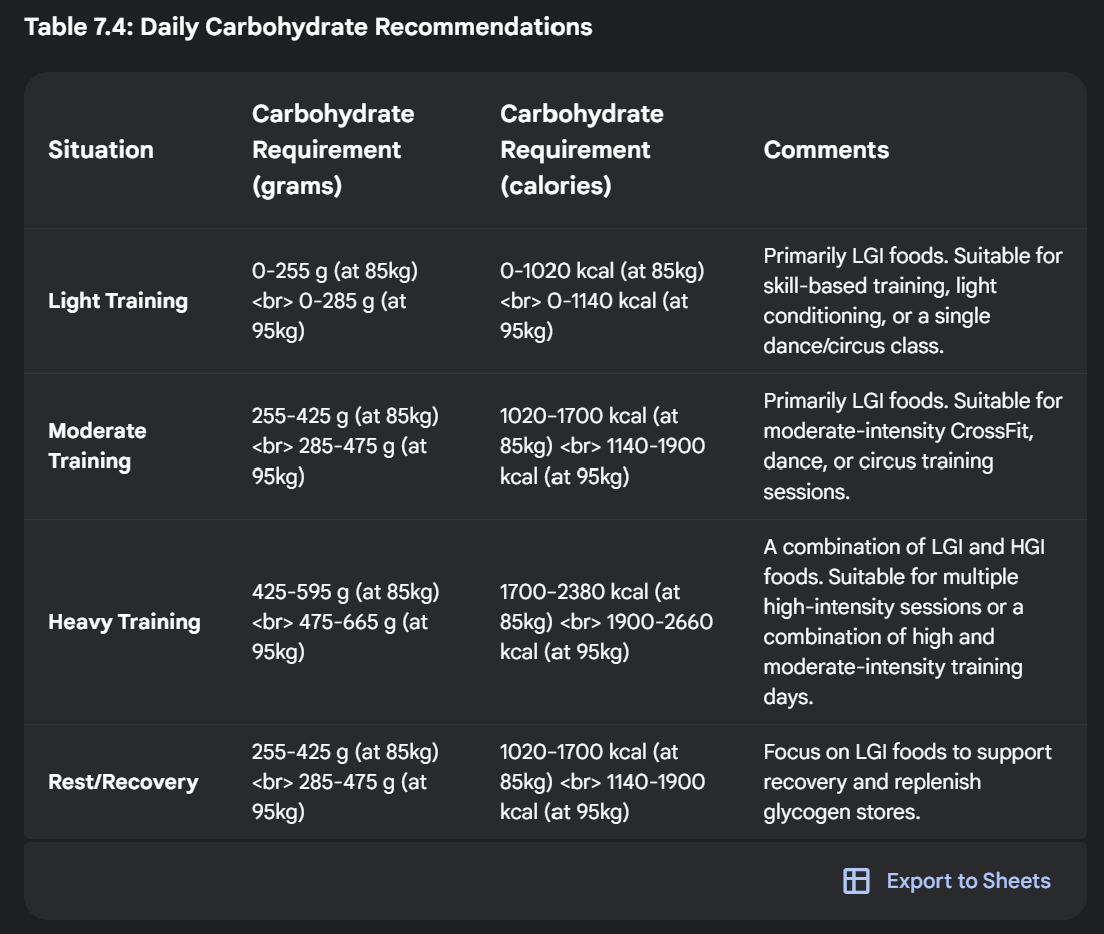

This is assuming I do have an RMR of 3500kcal per and the additional - alibet approximate - 3566 kcal burnt per week in my activities, that averages out to about 500 calories a day of extra fuel needed. Depending on the type of fuel needed, that will total to about 4000 kcal a day of activity. See table 7.4 for varying levels of carbohydrate intake depending on activities of the day.

Adjusting body composition towards 85 kg weight and 13% body fat

At this point we have an article that covers baseline nutrition, what to avoid, and provides a general guideline on how to adjust you carbohydrates, fats, and proteins based on the training load of the day. This should provide a foundational strategy for how to eat in a way that balances performance while also ensuring that I maintain a robust body that can sustain me for a long time. As of now, my body is good. I’m happy with its state but I’d like to adjust down based on my estimate for the body composition of an aerialist in the circus. The three main priorites are to -

Maintain existing muscle mass to ensure performance

Lose excess body fat via a caloric deficit

Facilitate quality training and learning of the circus skills

We estimate that I have a body fat percentage of 18%. That totals to about 17kg of body fat 78kg of muscle mass. I will have to get down to 85kg, leading to a muscle mass at 13% body fat of 74 kg and a fat mass of 11kg. So I have to cut down to that level losing less than 4kg of muscle mass and losing 6kg of fat mass. How do we do that?

The argument that Dr. Michael Israetel makes is straightforward. To reduce your weight, you need a caloric deficit measured as a percentage of your bodyweight. The argument goes that if -

you create a small deficit of 0.5% of BW per week (approximately .5 kilo per week)

you create a large deficit of 1%+ of BW per week or more (approximately 1 kilo per week)

For me, there is a range of .5kg to 1kg per week. How do you find the optimal range between those things? Michael Israetel suggest that you must meet three conditions, which we’ll call the survivability triangle:

1.) The food is high enough for high energy training

2.) Your sleep is still good

3.) Your hunger isn’t overwhelming

Thus, you can go UP TO AS HARD as these start to give. Easier is ok, but it might take a long time. So you can push your deficit to the bring of where #1 and #3 still hold true.

Notice the lack of caloric calculation in his analysis? This is markedly at odds with a significant amount of the calorie countin’ analysis above. Further than that, he recommends to set up a minimum weight loss goal that you go after every week given the above 3 conditions are still met on that week. Then stop the diet once that minimum weight loss goal can’t’ be hit while still satisfying the survivability triangle for two weeks straight. So if you set a goal of .5% (.5kg in my case) and you are still pushing hard on the survivability triangle deficit (ie. one of the conditions isn’t met).

Here is what I’m going to do with that. I will set a medium-easy go for myself as I’m still training for physical therapy recovery and aim for a .7 kg drop per week (1.5lbs approx.). That is approximately a 14-week diet to get down to 85 kilograms.

I will cut the food supply, which we’ll get into in a second, to match all three conditions. If I cannot meet the .75kg/1.5lbs goal while pressing down the deficit and staying within the survivability triangle for two weeks, I end the diet. This should bring me down to the desired body weight. But it still leaves the next question.

How do I avoid losing muscle?

This is a natural question. I want to lose 10 kilograms of bodyweight, with no more than 4kg of muscle mass being lost. To do so, I will up my protein intake and micronutrient intake while also paying attention to the survivability triangle.

From HPTFS -

… athletes should consume higher amounts - 1.3 to about 2 grams per kilogram of body mass per day - due to increased expenditure and physical demands….

…. the upper end of this range (or higher in some cases) should be used when in a caloric deficit (italics mine) to minimize the loss of lean mass (pp. 93).

So the baseline strategy is to apply the above weight loss strategy while still maximally accounting for protein intake as well as micronutrient intake through the form of nutrient dense fruits and vegetables. In this case, this means that I should start with the 190 grams of protein (50ish per meal, 4x per day) and aim to pass the 800 gram per day set-up for micronutrient consumption. This should provide an ample basis of nutrient to sustain me over the next 14-weeks as I go. Then we can return to a baseline nutrition (see table 7.4 for main carbohydrate change in daily calories) and adjust from there.

Putting it all together

I’ve set out to explain a baseline nutrition strategy and then layered in on top of it a strategy for how to eat for performance around a particular goal. In my case, I love the sacred combat in Crossfit and am aiming to build a body fit for performance at a high-level circus company. The approach is pretty simple. Eat whole food using the four pillars of nutrition and avoid most of the toxins that are bad for you. If you’re an athlete - or aspiring to be one like me - you have to adjust your caloric intake upwards significantly. In my case, I wish to balance circustry, CrossFit, yoga, and dance as my training inputs. Aim for simplicity first and don’t aim to count calories because the ability to do so is is not a science.

Now, in the beginning of the article I promised tactics, things that you could apply in your own life. So to close I’ll leave you with some suggestions:

Eat in accordance to the basics of the four pillars of nutrition

Remove all toxins from your diet, both general and specific to you. If you don’t know your specifics, go see a physician who can test for these.

Eat 800 grams of fruits and veggies on a daily basis

To adjust for sports nutrition do the following

Increase your protein intake to 2x your bodyweight in kilograms

increase fat to 1 gram to 3 gram per kilogram of bodyweight

Do the same for carbohydrates depending on the duration, frequency, and intensity of your training. Ask a nutritionist what the requirements of your particular sports will have upon your carbohydrate intake

If you’re trying to lose weight, good luck and figure out the method that works well for you as long as it doesn’t compromise your health.

This is what I am doing, and will do so into the future. So I wish you luck, health, and the fullest capacity of that fantastic body of yours.